the dark frisson of knowledge

on the Wikipedian sublime

For as long as I’ve been able to read, I’ve exhibited a certain but common type of intellectual pathology: an inexhaustable pursuit of information that arouses a nigh-hypnotic sense of anxiety. For me, the origins of this practice can be found in a childhood hyperfixation with the Microsoft Home edutainment game Dangerous Animals, which was a kind of interactive encyclopedia of Fauna That Could Kill You. This, paired with a set of obscure Disney yearbooks featuring articles about the Man-of-War jellyfish armed me with enough material to both unsettle my parents and self-soothe the emergent symptoms of attention deficit disorder.

Why I found an early pleasure in such material can be somewhat explained by a child’s sense of naive invincibility. I, a five year old, could definitely ride a lion to the grocery store. Unfortunately, though, a child starts growing up, and soon this odd behavior took on more psychologically aberrant qualities. For example, whenever the railroad crossing gates went down, I would scream hysterically at my parents to never drive around them. If an especially raucous thunderstorm rattled the rafters, you could find me cowering in the bathtub with my prized possessions (a pasture of Breyer model horses and my diary.)

These were normal childhood fears. But the older I got, the more I knew, the darker the fears became. In middle school, I lived in irrational terror that artificial sweetener would give me cancer. Roller coasters, which once thrilled me, became associated with a sudden and gruesome death. I spiraled around the idea of a White Noise-type chemical disaster, fantasizing endlessly about the imminent, invisible smog that would wipe out the meager population of my small town day by agonizing day.

Obviously, this behavior was becoming untenable, for both myself and everyone in my household. There were doctors’ appointments and breathing exercises and (in retrospect ill-advised) prescriptions for Zoloft. However, a key intervention came from a psychotherapist who suggested that my anxiety could be partially alleviated by knowing more about what was frightening me. At first, this was effective. After all, there had never been an airborne toxic event anywhere near where I lived. Millions of people around the country followed railroad crossing laws every day. Roller coasters were marvelously safe, given the intensity of their physics. The weather works in specific, impersonal and fascinating ways. (This itself became a years-long obsession.)

However, to the detriment of my therapist, a new, hybridized behavior began to emerge: learning information about mostly terrible things became both anxiety-inducing and satisfying. As soon as I was allowed a computer in my room, I trawled the online depths for new unsettling articles, overviews and histories. To this day, I can spend hours “in the info hole” reading about all kinds of nasty stuff: banned chemicals; tornado outbreaks; the fall of Lehman Brothers; the CIA. It doesn’t make me feel better. Nor does it make me feel abject panic. It makes me feel something else.

I’m not alone in this practice, of course. Anyone who’s looked at medieval manuscripts or binged 19th century crime novels knows that morbid fascination is about as old as humanity itself. However, in our internet age, access to information is unparalleled and expansive, which not only broadens the subject matter of morbid fascination and changes the practices of its consumption, but also diversifies, in ways subtle and unsubtle, the contours of feeling one experiences when consuming the content itself.

This latter point is probably obvious to those of us interested in media theory, but it’s still worth mentioning that the source or medium of this information changes the nature of its consumption. In terms of morbid curiosity, these differences are particularly visible in true crime, which blends the more lurid forms of human curiosity with spectacle and entertainment, most effectively in audio or audiovisual form. Even the written true crime exposé mimics the substance and tone of its televisual bretheren. Meanwhile, video essays and short form content, while sometimes adding new knowledge or interpretations of events, tend to present the same information found elsewhere (often infamously without citation) in more exaggerated ways. The reason for this is in part material — after all, YouTube is driven by revenue structures based on viewership and TikTok uses virality as a function of e-commerce.1

Even though it is now quite old, the primary vehicle for hoovering online information well into the night was initially —and for older generations remains — Wikipedia. The so-called “Wikipedia Binge” is a long-standing cultural phenomenon (and perennial Reddit joke), especially among millennials. But one must ask, beyond Wikipedia’s sheer availability as a source — why? In trying to answer this question, I’ve found that Wikipedia is remarkably unique in the way it shapes the affect and practice of both internet perusal and morbid fascination in particular. The reasons why range from structure to emotion. In scale, Wikipedia is seemingly infinite. In structure, it is taxonomic, and taxonomy is a very effective way of distributing larges batches of information at varying levels of specificity. Its informal encyclopedic tone spares the amygdala and allows for longer spells of dark perusal, while the feel of using it is a mix of focused, exploratory, and most importantly: private. Each of these qualities on their own make Wikipedia conducive to extensive browsing. But combined, they are especially effective when the content involved is frightening or extreme.

Pain and Danger

Before treading any further, however, one must ask: what exactly is this desirable yet negative feeling we get when going down the roster of worst floods in history or the grim details of nuclear radiation? Speaking as someone primarily devoted to aesthetics, the most useful framework for understanding this “negative affect” is the Romantic-era notion of the sublime — the sense of overwhelm, awe, and existential threat induced by objects or subjects that are vast, moody, infinite, laborious to produce, or otherwise magnificent.

The term was coined by one of my longtime theoretical frenemies, the empiricist (and arch-reactionary) philosopher Edmund Burke. Aside from lionizing the Bourbon kings and saying that the French Revolution wasn’t violent enough, one of Burke’s major philosophical projects was to both define this sublimity and distinguish it from beauty, to which he considered sublimity as being equivalent in emotional depth. The sublime is very useful in our discussion of grim knowledge for a number of reasons: it describes the affect itself, the necessity of distance in order to experience and understand that affect, and an aesthetic framework that can be applied to Wikipedia in both structure and form.

Burke’s sublimity is rooted in a belief that things that are “in any sort terrible, [are] conversant about terrible objects, or [operate] in a manner analogous to terror” create a more powerful and conflicting emotional response in the viewer than those that arouse pleasure. In his 1757 treatise A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful,2 he elaborated on the possibility that, contrary to common sense, satisfaction can still be found in such subjects if presented or interpreted the right way: “When danger or pain press too nearly, they are incapable of giving any delight, and are simply terrible; but at certain distances and with certain modifications, they may be, and they are, delightful, as we every day experience.” (Table the notion of proximal distance for now.)

To substantiate this, Burke used as some of his examples: the awesome perils of mountain passes, the terrifying endlessness of the ocean (despite the rational knowledge that the ocean, too, is finite), the drama of lighting in buildings and the toil that went into producing them. Immanuel Kant would later further refine Burke’s ideas by separating the sublime into two categories, the mathematical (a kind of magnitude that stymies our powers of comprehension) and the dynamical (the awesome power of nature and its ability to put us in danger.)

Though still sublime, mountains and seas were examples of Burke’s (and Kant’s) time, a time bound by horseback, the pen and the inkwell. In our own time, one must ask: is standing safely on the shore overwhelmed by Romantic-era thalassophobia really so different from bed-rotting and reading about deep sea diving accidents? Are one’s goosebumps from learning the sinister history behind the breakthroughs of the pharmaceutical industry so different from knowing that slave and peasant labor made possible the gothic cathedral? Is the sense of expansion one gets from opening a Wikipedian master list linked at the end of an article of infinitesimal obscurity really so different from the transition from cloistered candlelight to wide open landscape? We live in an epoch dominated psychologically and ontologically by information, with mediation as the primary way of interacting with the world. Does the flimsy barrier of hypertext really so alter the feeling of being pressed against the glass of human suffering and environmental fear?

Vastness

In addition to the pain and danger of the subject matter itself, many of the sentiments of the mathematical sublime can be mapped onto the Wikipedia binge as form, such as the monomania derived from a seemingly infinite source — here the repetition of the list.3 But of particular utility is Burke’s idea of vastness. In the treatise, he applied this primarily to the physical size and aesthetic configuration of landscapes as related to their individual elements. However, the concept, in our contemporary sense, can also apply to not only the sheer scale of human knowledge available for our perusal, but also the nigh Alpine effort of traversing this informational landscape. Like the content that makes up Wikipedia, vastness for Burke was not only about size, but specificity. About the natural world, he writes:

“…as the great extreme of dimension is sublime, so the last extreme of littleness is in some measure sublime likewise: when we attend to the infinite divisibility of matter, when we pursue animal life into these excessively small and yet organized beings…when we push our discoveries yet downward and consider those creatures so many degrees yet smaller, and the small diminishing scale of existence, in tracing which the imagination as well as the sense; we become amazed and confounded at the wonders of minuteness; nor can we distinguish in its effects this extreme littleness from the vast itself. For division must be infinite as well as addition; because the idea of a perfect unity can no more be arrived at, than that of a complete whole to which nothing can be added.”

One can choose to read a certain type of subtext here, that of a categorical and relational form of thinking. We can extend this thinking to the concept and practice of taxonomy — the gradual refinement of large categories into smaller ones by way of shared characteristics. Here the scale of the total “landscape”, analogous, perhaps, to the Wikipedian “category,” is broken up into fragments that share relations to other fragments in both the broad and narrow sense.4

At its core, even today, the internet is a series of lists, of pages linked to other pages. Our contemporary non-linear, algorithmic, and dynamical internet obscures this list-based structure to the extreme, driving new kinds of both passive and participatory consumption: the endless scroll, the chatbot conversation, the feed. Wikipedia, however, is one of the few large websites still devoted entirely to reading and text, whose Web 2.0 configuration of nesting links retains the old logical substrate of taxonomy and the ensuing practice of taxonomical thinking. When we consume the topics of morbid fascination on Wikipedia, we are actually consuming taxonomies of these topics. The binge is the pursuit of the last branch of the taxonomic tree.

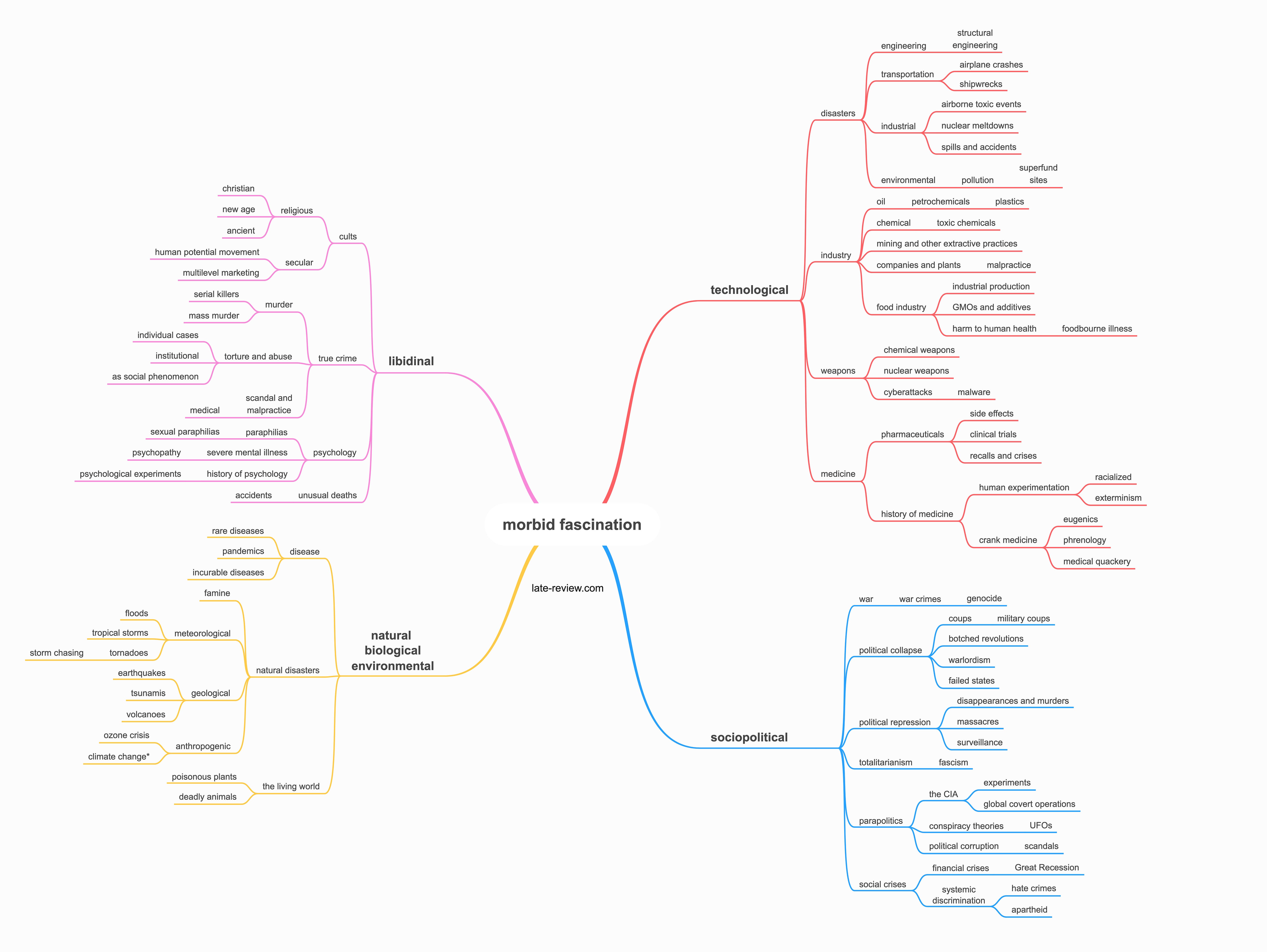

Ultimately, one could say that fear itself is, through Wikipedia, taxonomized — that through the binge we experience fear at differing scales and different subsets of sublimity that make excess browsing emotionally rewarding. These fear taxonomies are unique to every user, but it’s worth devising a hypothetical one covering most of the bases of morbid fascination to illustrate our point. (I realize this is a large image — mobile users can pinch and zoom.)

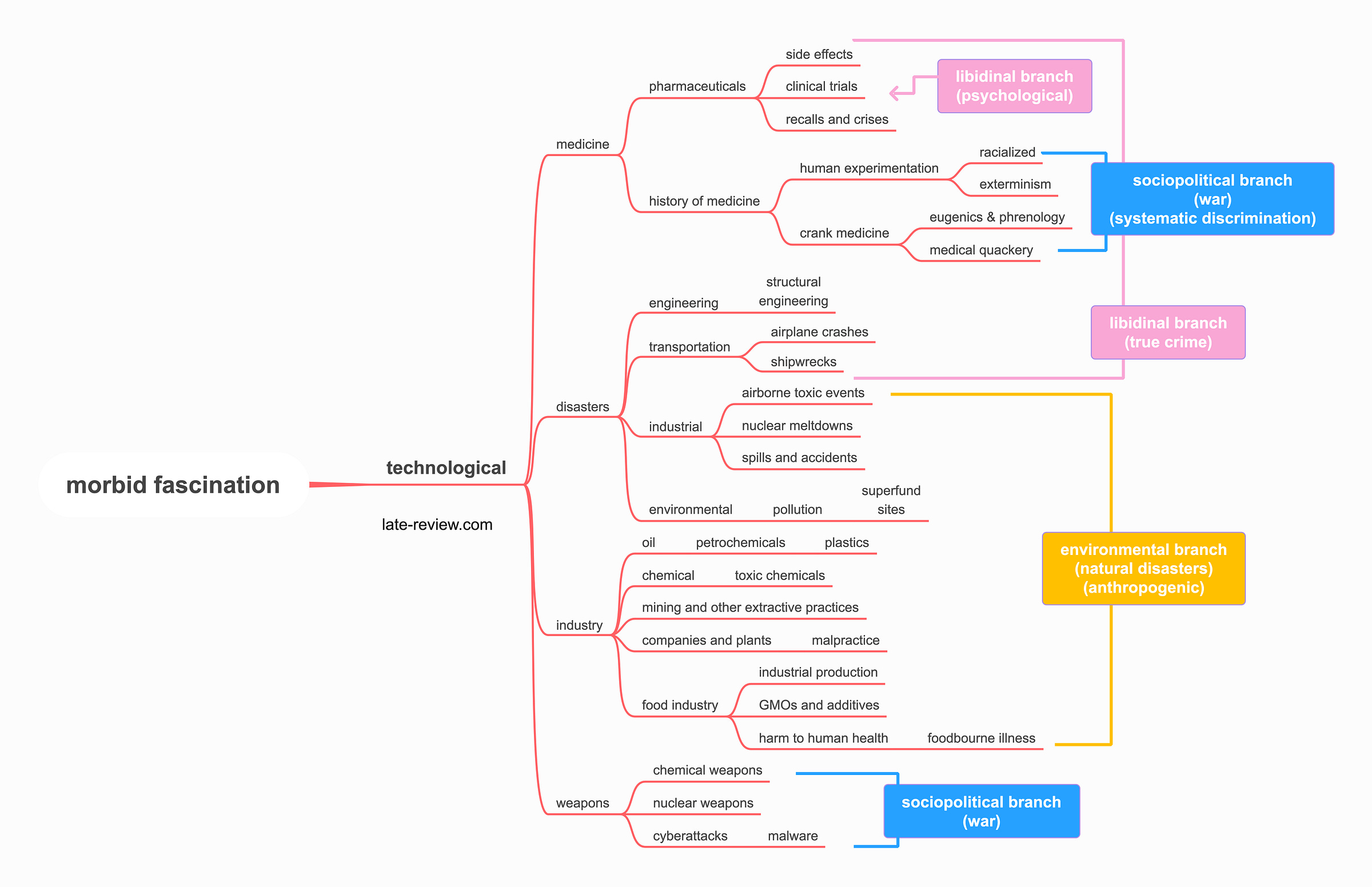

What makes Wikipedia both endless and infinitesimal is the intersection of any given taxonomy with another. The rabbit hole is not only deep, it is connected to a warren. Viewed in another way, we can see the flows between fear trees, trees that both expand and contract in scale, forming the uneven composition of a landscape in their own right.

Beyond form, each of these four general quadrants possesses subtle differences in affect which are, on their own, conducive to certain patterns of browsing. For example, I call the top left branch “libidinal” because it deals with human drives and stimulates that part of the psyche that wants to understand the depths (and depravity) of the individual human subject. Here we find the unknown mind and the weakened body, the true crime penchant for the sublimation (and often eroticization) of violence, and varying forms of interpersonal control. Large-scale crimes and societal ills filter down into individual perpetrators which themselves re-dilate into broader pathologies.

Alternatively, we can find the full extent of Kant’s dynamical sublime in the environmental division of the chart. This branch is dominated by massive, earth-altering events — events in which thousands of people have been imperiled, whose commonalities are best sorted by the number of casualties. The technological sublime is of course the most expansive, touching practically every element of our lives, from what we eat to how we travel. Technology itself is a series of tools shaped by human desires and human flaws, each prone to failures as big as a landscape and as small as the contents of a petri dish. The mechanisms of danger within different categories of industrial technology are particularly far-reaching and diverse; all of it is rooted in the inescapable power of modernity. There have always been wars, floods, and murders, but thalidomide is relatively new. Finally, Burke’s penchant for both grand and granular political violence is on full display within the sociopolitical branch, which, as any good materialist knows, is a labyrinthine synthesis of everything else.

Distance

Taxonomical thinking combines with another element of sublimity to complete the Wikipedian experience: distance. Burke’s idea was that a certain distance from the subject largely facilitates our feelings of delight towards what would be otherwise terrifying. It’s a feeling of: these things can hurt you, but they probably won’t. The probably is somewhat important, as one of the things I’ve noticed in my own browsing history is a repeat need for temporal distance from any given topic of morbid fascination. In the diagram, I put an asterisk next to climate change because I (and many others) don’t find it pleasurable to read about a subject that will have profound consequences for my lived experience. There is further safety to be found in knowing that an event has reached its historical conclusion. Even in narratively open examples such as cold cases, the longer the temporal distance from the event, the more possible it is to derive sublimity from it.

More specific to Wikipedia itself, however, are the site’s tone and user interface. The tone of Wikipedia is impersonal and, well, encyclopedic. This encyclopedic tone is effectively anti-spectacle and emotionally narrow, allowing for even the most upsetting of subjects (such as the Bhopal disaster or Nazi Germany) to be held at arms length. This tone not only facilitates the prolongation of the browse — one’s cortisol levels aren’t totally blown out — it absolves it. After all, it is somewhat embarrassing and oft considered unhealthy to spend hours reading about wretched things, which is perhaps why people call true crime a ‘guilty pleasure.’ But the flat tone of Wikipedia and its context as a credible source allow the binger to feel as though their binges are educational. In other words, Wikipedia legitimates lurid obsession by concealing it in the veil of learning.

The old-internet interface of Wikipedia complements the work of its tone in sustaining this dark momentum. Wikipedia is one of the last what-you-see-is-what-you-get large websites. It is only (to reiterate) an indexical list of lists. Because the site is a non-profit and collective effort, it has no advertising, no social element, and no other common forms of user distraction. Thus, its overall effect is that of separation — or perhaps insulation — from the outside internet, the outside world. The bannerless blankness of the page’s margins, the lack of any movement, the repetition of lines of text— it all gives the user a feeling of being alone with their fascinations; a sense of privacy. In our age of platformization, one cannot escape the feeling of being surveilled, either by advertisers, Palantir, or by one another. In contrast, the respite Wikipedia still offers us is a powerful one.

I wrote this essay because, a few nights ago, it was 1 AM and I was reading. That’s normal for me these days. Despite having mostly recovered from the brain injury I sustained in January, I’m unfortunately still experiencing severe insomnia and mood disturbances. Earlier that afternoon, my doctor, not wanting to prescribe benzodiazepines or Z-drugs, wrote me a script for Seroquel hoping to treat both sides of my problem. It was too late in the day to fill the order at the pharmacy, which, to my delight, gave me an opportunity to obsess over it. Safely cocooned in the the darkness of my bedroom, the light of my phone, mitigated somewhat by the blessings of dark mode, soon washed over my slowly flicking thumb.

Quetiapine (/kwɪˈtaɪ.əpiːn/ kwi-TY-ə-peen), sold under the brand name Seroquel among others, is an atypical antipsychotic medication used in the treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, bipolar depression, and major depressive disorder.

Seroquel, a few more scrolls will tell you, was patented alongside many other psychiatric drugs in the 1990s. It is considered to be well-tolerated compared to its predecessors in the typical antipsychotic family. The side effects, however, can still be nasty, especially at higher doses or when the drug has been taken for years at a time. The most concerning side effects include weight gain — which itself can trigger something called

Metabolic syndrome is a clustering of at least three of the following five medical conditions: abdominal obesity, high blood pressure, high blood sugar, high serum triglycerides, and low serum high-density lipoprotein (HDL). —

and extrapyramidal effects

In anatomy, the extrapyramidal system is a part of the motor system network causing involuntary actions. The system is called extrapyramidal to distinguish it from the tracts of the motor cortex that reach their targets by traveling through the pyramids of the medulla.

some of which can be severe, such as

Akathisia (/æ.kə.ˈθɪ.si.ə/ a-kə-THI-see-ə) is a movement disorder characterized by a subjective feeling of inner restlessness accompanied by mental distress and/or an inability to sit still. Usually, the legs are most prominently affected. Those affected may fidget, rock back and forth, or pace, while some may just have an uneasy feeling in their body. The most severe cases may result in poor adherence to medications, exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms, and, because of this, aggression, violence, and/or suicidal thoughts.

and

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is an iatrogenic disorder that results in involuntary repetitive body movements, which may include grimacing, sticking out the tongue or smacking the lips, which occurs following treatment with medication.

Anyone who’s read about drugs on Wikipedia knows the drill from here on out: the long, tedious sections about the complex mechanism by which the medication works, its unfathomable chemistry, a brief overview of its development. Then, at the bottom of the page: that dreaded yet delectable section devoted to controversies. Seroquel was not left unscathed by the usual evils of the pharmaceutical industry. Per our Wikipedia page: In April 2010, the U. S. Department of Justice fined AstraZeneca $520 million for the company's aggressive marketing of Seroquel for off-label uses. Apparently, the feds later uncovered that the company had gone so far as to hire doctors to ghostwrite medical studies that weren’t actually conducted.

But beneath this, one can find something even worse.

Dan Markingson (November 25, 1976 – May 8, 2004) was a man from St. Paul, Minnesota who died by suicide in an ethically controversial psychiatric research study at the University of Minnesota.

The article is long, so I’ll paraphrase. In 2003, Markingson experienced his first episode of severe psychosis while trying to cut it as a screenwriter in LA. His mother managed to coax him back to his hometown of St. Paul, where he was treated by a certain Dr. Stephen Olsen, a professor in the U of M psych department. After first submitting a petition to have Markingson committed in a long-term psychiatric hospital, Olsen seemingly changed his mind and had Markingson instead pledge himself to a U of M treatment plan.

The plan was actually a cover for something else. Olsen asked his still very infirm patient to participate in an AstraZeneca study studying the efficacy of different atypical antipsychotics including Seroquel. All the legal paperwork was taken care of without informing Markingson’s caregiver, his mother. Even worse, Markingson’s participation in the study was not entirely voluntary — should he discontinue it, the doctors threatened him with the original permanent commitment.

In the trial, Markingson was given Seroquel, which made his condition worsen significantly, much to the urgent concern of his mother, whose cries went unheeded. It was only a matter of weeks before he killed himself by slitting his throat open with a box cutter. Ultimately, after a long and arduous accountability process — including an internal probe that found over forty ethical violations within the University of Minnesota’s psychiatry program — the university denied all wrongdoing, and would continue doing so for more than a decade. Despite this, the case set off a wave of reform attempts both legally and within the pharmaceutical industry. It has since become a lodestar of bioethics.

3 AM came. Sufficiently worn out, I rolled over and shut off the phone, thinking all that stuff happened years ago. I don’t have schizophrenia. My prescribed dose of Seroquel is low and its use temporary. But, as my body continued to deny me sleep, the more I ruminated on what I’d just done to myself. Why did I need to pursue this dark frisson of knowledge? Why did I feel both tense and enraptured when peering into the internet terrarium of the worst of all possible worlds? But spending the last two hours reading about Seroquel and metabolic syndrome and extrapyramidal effects and Dan Markingson — deep down it was my little secret. I did it because I wanted to. Maybe you, deep down, want to read about it, too. And why not? Nobody will know. Nobody has to know, either. It’s just you, only you, and the hole.

It’s also worth noting of course that some content creators reinvent morbid fascinations in new and entertaining ways — for example the podcast Well There’s Your Problem (on which I have been a guest), while still being grounded in expertise, adds both sociality and a darkly comedic twist to engineering disasters.

Edmund Burke, from A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757) in The Works of Edmund Burke, Vol. I, London: G. Bell & Sons, 1913, pp. 74–5, 100–8.

On the idea of infinity: “[M]admen…remain whole days and nights, sometimes whole years, in the constant repetition of some remark, some complaint or song; which having struck powerfully on their disordered imagination…every repetition reinforces it with new streight; and the hurry of their spirits, unrestrained by the curb of reason, continues it to the end of their lives.”

The interconnectedness of content on Wikipedia is demonstrated in the once-viral “Homer Simpson” game — the idea that it is possible to start at any non-stub English Wikipedia page and, through the linking system, arrive at the Wikipedia page for Homer Simpson. The game is won by doing this in as few clicks as possible.

It is a fact of set theory that the number of infinities (i.e. set cardinalities) must be larger than any particular infinity. But whether anything physical is infinite, either in divisibility or extent, is an open question. Infinity, perhaps paradoxically, makes the mathematics we use to describe our world more tractable; but that does not in itself make it true.

Curiously, many ancient Greek mathematicians, if I am reading Jacob Klein correctly, thought the opposite: the physical world is infinitely divisible but numbers are not. What we think of as the number one, they thought of as a special category, the monad, a kind of numerical atom distinct from the other numbers (arithmos.)

Okay, so this is basically me and anything related to nuclear warfare: weapons, strategy, civil defense, effects, rebuilding...