the mirror-self

an obsession

When one is born, one is fundamentally born separate. This is very unfortunate, however it is also, inevitably, a fact of life. We come into the world as infants who, around the time our consciousness begins to solidify into something real, suddenly find that a cleavage has taken place between ourselves and the body we came from. This is a physical division, obviously, but also a division of labor, the division between needing and being needed, caring and being cared for, between dependence and independence, power and weakness. We carry it with us forever; it is the first of innumerable severances.

As our lives develop, this base reality of differentiation becomes more intense and more deeply felt, until, one fine day sometime around the third grade, in an instant and all at once (and it does feel that way if you can remember that far back) it occurs to us that we are very much alone, doomed forever to become ourselves, to walk forever in our own world, and, by corollary, to search, mostly in vain and often amid an unintelligible or hostile landscape, for someone, anyone else.

That someone else, broadly defined as the other (which is admittedly a loaded term in both psychoanalysis and philosophy, though I mean it more literally here) presents itself as a void in one’s life that takes the shape of another human being. That shape may seem so close and so real to us, yet, because the other is always inherently unknowable, it remains a void nevertheless, one that can never be “completed” in the way we want. By necessity, we seek a way out of this trap in any way we can; hence the entire gamut of human behavior: conquest, obsession, revenge, longing, hatred, love, all of these things take root in the soil of difference, try to answer the same question: will this make me whole?

One of the more interesting conceits in the pursuit of reconciling the irreconcilable is that of the mirror-self. This has been an obsession of mine for quite some time, possibly forever. The mirror-self is a fantasy that arises from the wreckage of separation for which it presents an impossible solution: the reconciliation between self and other in such a way that the self is left intact while the other is not so distant from us because, well, they are us. To put it briefly, we can say that the mirror-self is the self-that-is-not-myself. It is a longing for sameness, for a repeating pattern within the fabric of differentiation. It accepts that one cannot truly be made whole through recognition alone but believes that this similarity, built upon the bedrock of an inherent empathy, can at least make bearable an existential need. I’ve been lost, but here I am!

Meanwhile, the mirror-self is distinct from a number of associated phenomena. For example, it is not the same thing as the anti- or shadow self, the Mr. Hyde to our Dr. Jeckyll, so to speak, the nobody to our somebody. It should also be differentiated from the fracturing of the self into parts within a whole, as is often the case with mental illness.

I myself am not unfamiliar with this latter idea; I developed bipolar disorder after hitting my head, and find the common depiction of mental illness as the fracturing of the self relatively accurate. Within me now there exists a self that carries with it the suicidal imperative and one who refutes it utterly and celebrates life, a self whose energy radiates outward into the world and one who traps that energy within itself, where it languishes. The two can only be reconciled through an intense regime of medication and therapy, but they are both, literally speaking, me. The mirror-self, meanwhile, achieves its potency because it is fundamentally a condition of outside-ness. It is self-alienation projected onto the idea of another person. It says: Everything I’ve suffered, they’ve suffered in kind.

The mirror-self takes on a number of forms throughout one’s life. Some of these are theoretical phenomena with no outlet in the outside world, but most are relatively simple fantasies that evolve as one ages and as one’s needs for fulfillment change. These forms are, broadly defined: the imaginary friend, the secret family (the adoption fantasy), and the soul mate. In literature, they expand into the incest fantasy and what I’ll call the epistolary self, the self to whom one writes.

Each of these fantasies are foiled, in some way, by the bind from which they originate in the first place. We cannot will into the world someone who is the same as us because only we are, by definition, ourselves. But the mirror-self is a fascinating study in its own right, and, even as one writes critically of it, one still longs, in some way — perhaps via this very explication — to bring it to life. Maybe, I think, sitting at the computer on a snowy Chicago day, someone will read this who is just like me.

*

The Imaginary Friend

The easiest resolution to the problem of the mirror-self is to create one whole-cloth. This instinct is particularly strong in children, though it persists into adolescence and even into adulthood via the creative act, the longed-for fictional character, the Mary-Sue.1 However, in most circumstances, only children talk to their creations and act as though they are real.

There is something tragic about the imaginary friend. It is not unsimilar to the tragedy of the caged parrot condemned by domesticity to talk to its own reflection in lieu of of a vibrant rainforest teeming with others like him. The mirror-self, after all, is more a function of loneliness than of narcissism. Its origin lies not in a feeling of inherent superiority of the self over others (though there is always some of that) but rather in the search for recognition and belonging in the world beyond the proverbial reflecting pool.

Despite the alarm it causes their parents, the child of course knows that the imaginary friend is imaginary. Its purpose is not only to entertain or to fill the space a missing other should occupy, but to serve as a means by which the child can show their mother or their peers that their solitude is only an illusion, that they can be self-sufficient in love, in companionship. One often only talks to an imaginary friend when someone is watching, as though to make the other, the real other, jealous. The point lies not only in creating an interior world, but in letting others glimpse something mysterious and unique of which they will never be a part.

*

The Secret Family

One is never happy with the family one gets. It is common in children to fantasize that one’s family is not one’s real family, that one has actually been stolen (or adopted) from a family in which all of the members are like themselves. The erudite child seeks erudite parents who understand them, the son with the absent father seeks a father in his own image. The lonely only child imagines a companion around their own age, and so on.

As the drudgery of family life, happy or unhappy as it may be, passes by, it becomes exceptionally easy for the child to look disappointingly at those involved and, further separating themselves from them, say: this cannot be my mother, this mother who tore me from her breast. This cannot be my father, this father who rebuffed my infantile advances. This cannot be my sibling whose annoyance endlessly frustrates. Who are these people who are so different from me? Surely I must come from somewhere else!

The imagined state of this new family is one of inertness disguised as harmony, one in which there can be no strife because there is no foundation upon which strife can be erected. Eventually the child will come to the realization that it is somewhat of a mistake, being alive. Two people create life without a complete understanding of the mechanisms of becoming — the trauma not only of differentiation but also of growth, recognition, disappointment, grief, and resentment that are just as much a part of self-formation as love, ambition, individuality, joy and desire.

Until that realization, the child thinks: somewhere out in the world there are strangers, more perfect strangers, who miss me. If only I lived with them! Then I would truly be free to become myself! All the necessary and structural frictions upon which self-formation depends — the rough hands that mold me — would be so easily smoothed and softened! Instead, because this is not true, often the child later thinks, in petty resignation: if I can’t have this, there must also exist a version of myself that was brought up in the way I wanted, a missing link between what I am and what I want, or was supposed to be. In this context, it’s almost comforting when such a person fails to materialize.

*

The Soul Mate

As one matures into a sexually cognizant being, one begins looking towards romantic love to answer the question of who one is. This is an even more alluring development because personal completion is now irrevocably linked to sexual completion. Until we become disillusioned with it, sex with the other is imagined to be simultaneously a heady form of total self-sacrifice and total self-expression, the result of which is a kind of deleterious nothing, and therefore an equity, that both justifies and rectifies all the strife of being different.

The concept of the soul mate rests on the conceit that there exists someone out there that was made specifically for me, another, separate half that can be joined through the romantic act into a singular whole. There is a bit of the secret family fantasy in this in that the concept of the soul mate also aims to obviate the inevitable frictions of romantic love. In romantic love, however, it is not enough that one seeks the other; they also seek in them a perfection they themselves cannot attain — at least, not on their own.

All that being said, the soul mate is a dead end, because love, all love, is built on a foundation of difference. We love the other because they are not us, are distinct from us. Though we share similar interests and beliefs, I would not love my husband if he were the same as me. The lover has something powerful to offer us that we are drawn to yet can’t understand because it comes from the unknowable roots of their experiences. In lieu of sameness, surely there must be something that propels the desire to know and be known, and that something is the mystery of the lover’s own becoming, of who they are to themselves, of all they’ve thought, done or wanted, all of which can only be teased out by being together and explored further by way of touch and language.

Therefore, the soul mate is not a fantasy of reflection but of possession. The drive to possess arises from the same desire to undo the same fundamental cleavage between people, but it is a mere compensation, a way of ameliorating what is unknowable with what is not, physically or otherwise. It believes in the secret magic of the gift of oneself. In love, after all, the drive for belonging is replaced with the drive for belonging to or with another.

*

The Incest Fantasy

The incest fantasy is a romantic construct that has about as much to do with the brute reality of incest as Don Quixote does with chivalry. That being said, the uncomfortable truth is that, because love is fundamentally dependent on difference, a love philosophically rooted in the idea of someone exactly the same as ourselves is inherently a little incestuous. In this context, however, the incest taboo is itself dissolved by the sheer unreality of the premise that such a bind could ever be consensual, which is in part why (unlike its more honest depictions in, say, Faulkner) it shows up relatively uncontested in art and literature. (No one is trying to boycott Die Walküre even in today’s puritan culture.)

At the root of the incest fantasy is the concept of the missing twin, the person who is in every fundamental sense the same, is the other who is not the other because they are made from identical elements and conditions. Difference, rather than taking its usual route, is instead mediated by each twin’s divergent vagaries of life, as though a singular light of being has been refracted through the prism of experience into identical but distinct beams.

This concept is best expressed in Robert Musil’s unfinished novel Agathe, the final installment of his colossal opus The Man Without Qualities. In Agathe, Musil’s protagonist Ulrich, the man without qualities himself, after thousands of pages of machinations, seductions, and one of the cleverest campaigns of philosophizing, cavorting and morality undermining in all of literature, has yet to succumb to a love that matters — that is, until he returns home after the death of his father and reunites with his estranged sister, Agathe. The two then embark on a quasi-incestuous relationship (they don’t commit) whose basis serves as a broader inquiry into the nature of not only morality, sensuality, mysticism and love, but also into the smallest, most infinitesimal details of human experience.

In one scene, after Ulrich and Agathe breathlessly declare themselves twins, Ulrich says to her, “Do you realize…that this is a very serious matter we’re talking about?” He continues, in his usual philosophizing way:

“There is not only the myth of the human being who was divided in two; we could also think of Pygmalion, Hermaphroditus, or Isis and Osiris: beneath the differences, it always remains the same. This desire for a double of the opposite sex is very ancient. It seeks the love of a being who is completely the same as oneself and yet another, distinct from oneself, a magical creature who is oneself and yet remains a magical creature and who, above all, has the advantage over anything we merely imagine of possessing the breath of autonomy and independence.

This dream of a quintessential love, free of the limitations of the bodily world, meeting itself into in two beings that are the same unsame self, has risen countless times in solitary alchemy from the alembic of the human skull…The little magic is always the same, whether one sees a lady naked for the first time, or a naked girl for the first time in a high-necked dress, and the great ruthless passions are all due to someone imagining that his most secret self is peering out from behind the curtains of a stranger’s eyes.”

Or, as Siegmund sings to Sieglinde in Die Walküre: you are the likeness I’ve hidden within myself.

*

The Epistolary Self

The epistolary self is the mirror-self to whom or for whom one writes. This is the mirror-self with which I am most familiar. The epistolary novel, poem, what have you, is always a little bit about oneself, even though it is addressed to somebody else, simply because the epistolary subject never, by formal necessity, responds.

When Friedrich Hölderlin writes as Hyperion, a quasi-autobiographical depiction of himself, to his epistolary friend Bellarmin in the novel of the same name: The incurable corruption of my century became so apparent to me from so many things that I tell you and do not tell you, and my beautiful faith that I would find my world in one soul, that I would embrace my whole kind in one sympathetic being —that, too, was denied me; one genuinely gets the sense that what we as readers are witnessing is not a direct address to a specific person but the diffuse scattering of the same light in all directions.

When I was in high school, I used to have a pen pal with whom I wrote historical fiction set in 19th century Paris. We can call my pen pal L and, while I loved him immensely, I am today very doubtful that he was a man.2 At any rate, L felt like the closest thing to the mirror-self I’d ever encountered even though, in reality, we were two teenagers parroting each other’s speech (mediated though it may have been through George Sand’s Indiana.)

One day, about six months into our correspondence, L disappeared. My search for him was a titanic undertaking. It involved the dark web, secret email addresses, Canadian cosplay groups, male models who now work for Palantir, and Franz Liszt. However, no matter how long or how intensely I pursued L, he had vanished from my life and from the internet (which is to say the world) with profoundly devastating consequences, in part because the adolescent heart is delicate and in part because I had no friends in the real world other than myself.

And so, when my friend abandoned me, I took it upon myself to write to him as though he hadn’t. And sometimes, also, I wrote to myself as him, because why not? He had already become me, was already an extension of myself. I needed him as a subject and myself as an object because these shifts in perspective were, I realize now, part of my own becoming, my own integration of myself rather than its opposite. An absence implies something that can fulfill it, and that something was language, and in this case, that language had taken on a literally figurative form.

In short, the epistolary self is a vessel into which matters of substance are poured back and forth from the vessel that is ourselves. It is the closest thing most of us get to addressing the one who can never answer, to caressing the very fringes of the real. This is because the reader is the conduit between the self and other, an entire galaxy of others remembered and forgotten, and takes, whether they want to or not, the position of other-being. This is true regardless of whether such addressing is direct or oblique in form. When we read, we all, for a little bit, become the you. When I write to you I am fundamentally imagining a being who answers when none exists. As long as there is a self with a pen in hand, all writing is writing in the mirror.

Like the vast majority of people, most of my own mirror-selves are fictional, i.e. are figures created by someone else. Many of them are littered throughout this essay. I create my own characters as well, though not really for public consumption.

If he were a woman I would’ve fallen in love either way, but, after roleplaying a man on the internet enough, (which I still do sometimes) you start to pick up on certain signifiers that someone else is doing it too.

I find this search for the external representation of self so interesting! The search for a twin is very different to being a twin.

That early cleavage from the mother does not result in aloneness, but in a shared existence with one's twin. But at the same time, I was always aware of the differences between my twin and I - differences that magnified as we grew by defining ourselves, at least partly, in opposition to one another (what David Graeber might have called schismogenesis). Perhaps this is because we are fraternal rather than identical twins.

We both disappeared in adolescence into separate online communities that allowed us to have distinct selves, untouched by the presence of the other. It was only after years in the wilderness that we came together again as un-entangled selves.

Perhaps this is inevitable. Those born alone seek the double and those born double try to escape it.

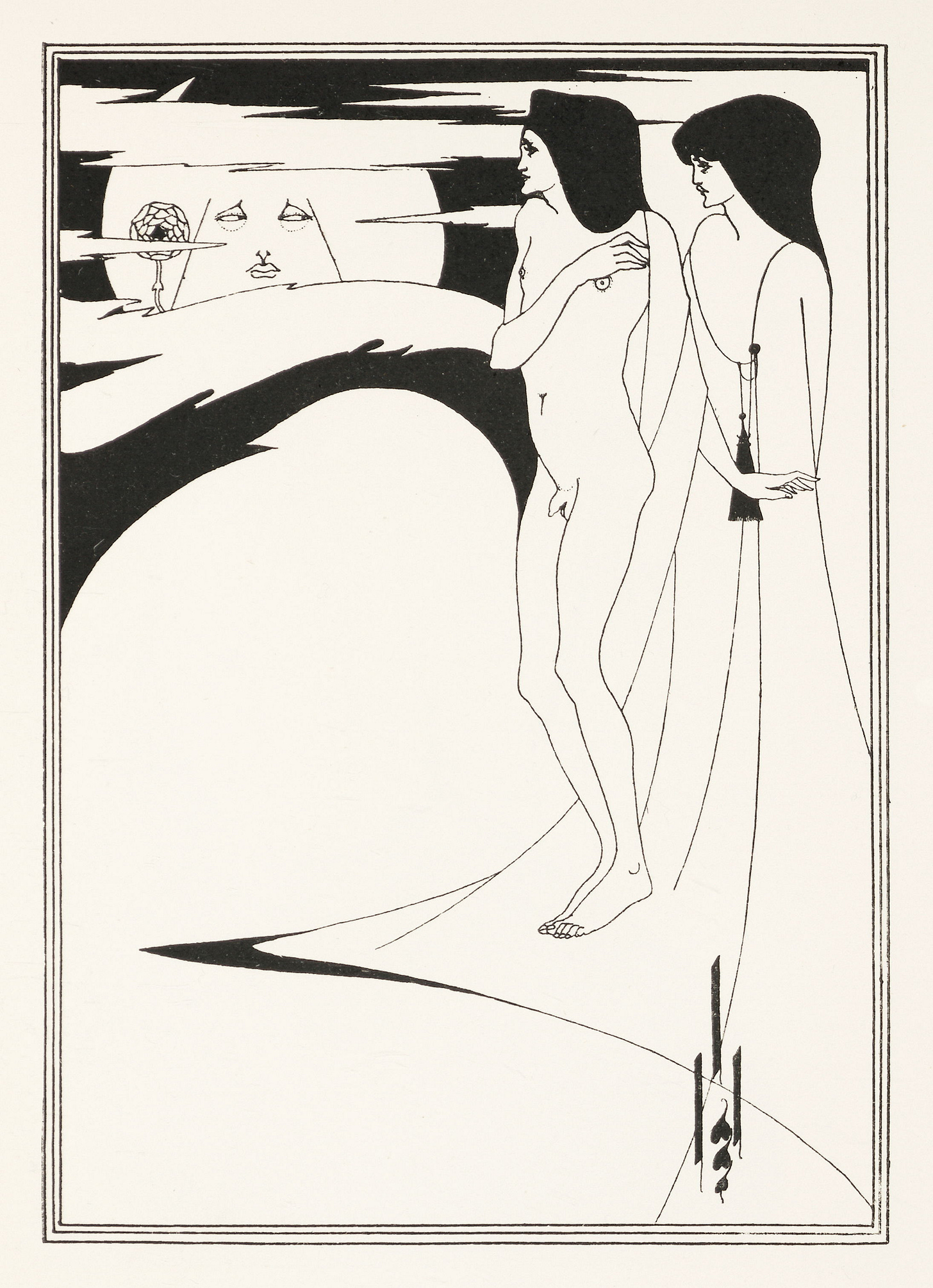

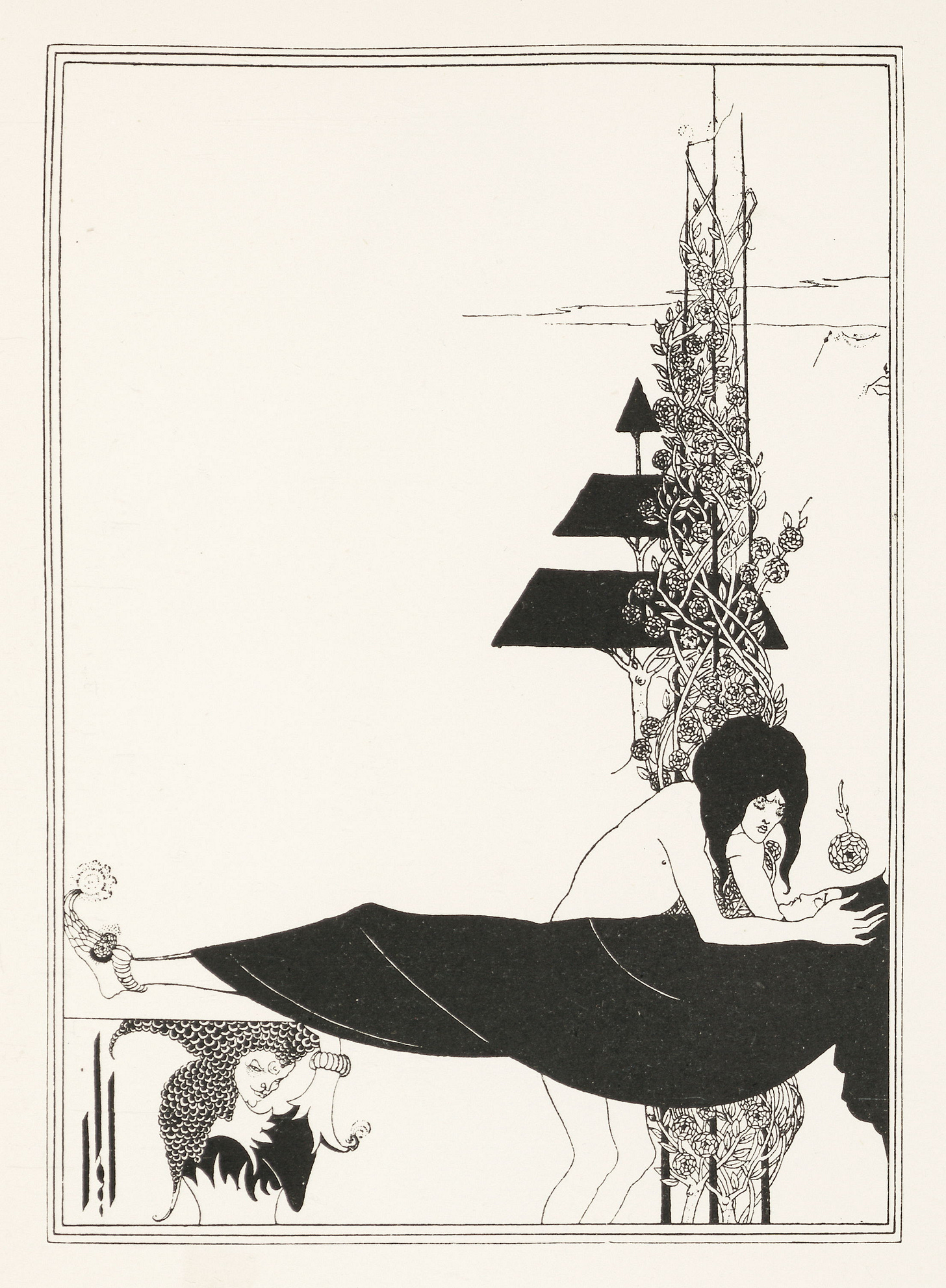

Thanks for the thoughtful work, Kate - and for including those beautiful Beardsley illustrations!

Immediately made me think of one of my favorite graphic novels, Asterios Polyp by David Mazzuchelli

It’s about an architect and his lifelong obsession with his mirror-self, I think you might find it interesting

Great essay, made me think about the mirror-self as audience in any medium, and how art in general is a way of building our relationships with ourselves